CONSCIENTIOUS JUDGE OR HACK?

Staten Island DA’s Close Ally Ray Rodriguez Faces Firestorm Over Motion to Step Aside

NOTE: This piece first appeared on NYNewsPress.com.

By M. Thomas Nast

The McMahon’s Personal Judge

Up for re-election this November, Judge Raymond Rodriguez is under fire for presiding over a case involving his long-time friend and political ally, District Attorney Michael E. McMahon.

On July 29, journalist Richard Luthmann filed a detailed motion seeking Rodriguez’s recusal from SCI-90073-20/001. Luthmann claims Rodriguez cannot remain impartial because McMahon is the complainant.

“Judge Rodriguez has publicly acknowledged a close personal and professional relationship with District Attorney McMahon and his wife, Justice Judith McMahon, that spans approximately 30 years,” the affidavit states.

In a May 2025 interview, Rodriguez bragged about “capitalizing” on that relationship upon becoming Administrative Judge. He even praised the decision to put Judge McMahon in charge of a jury part.

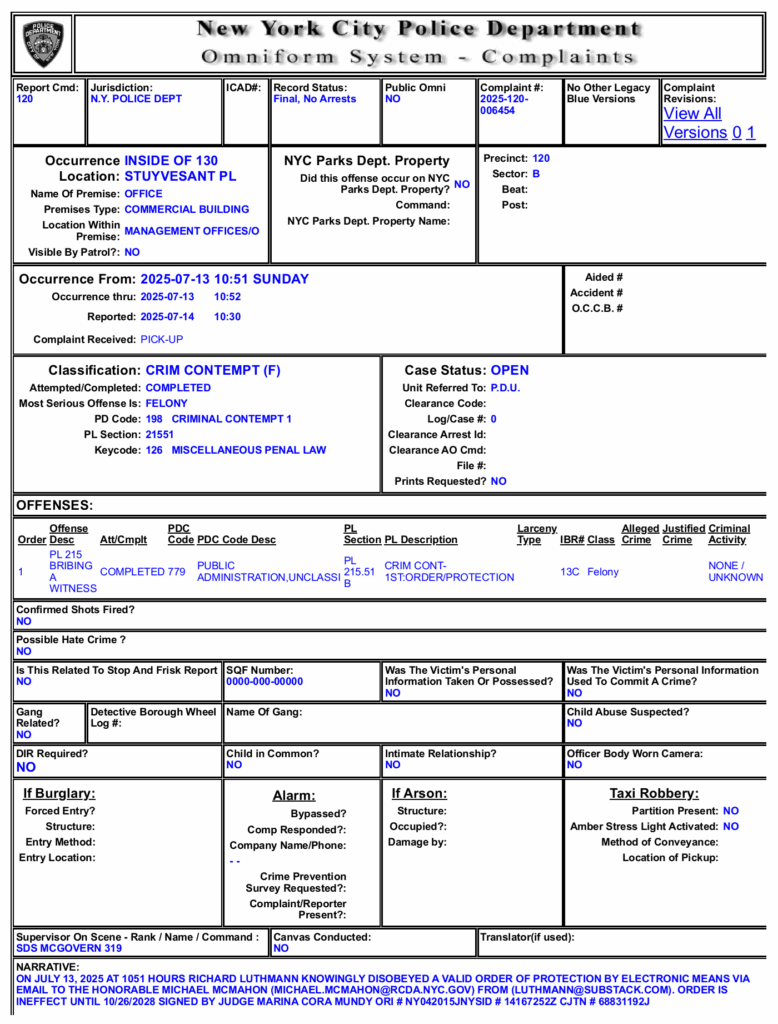

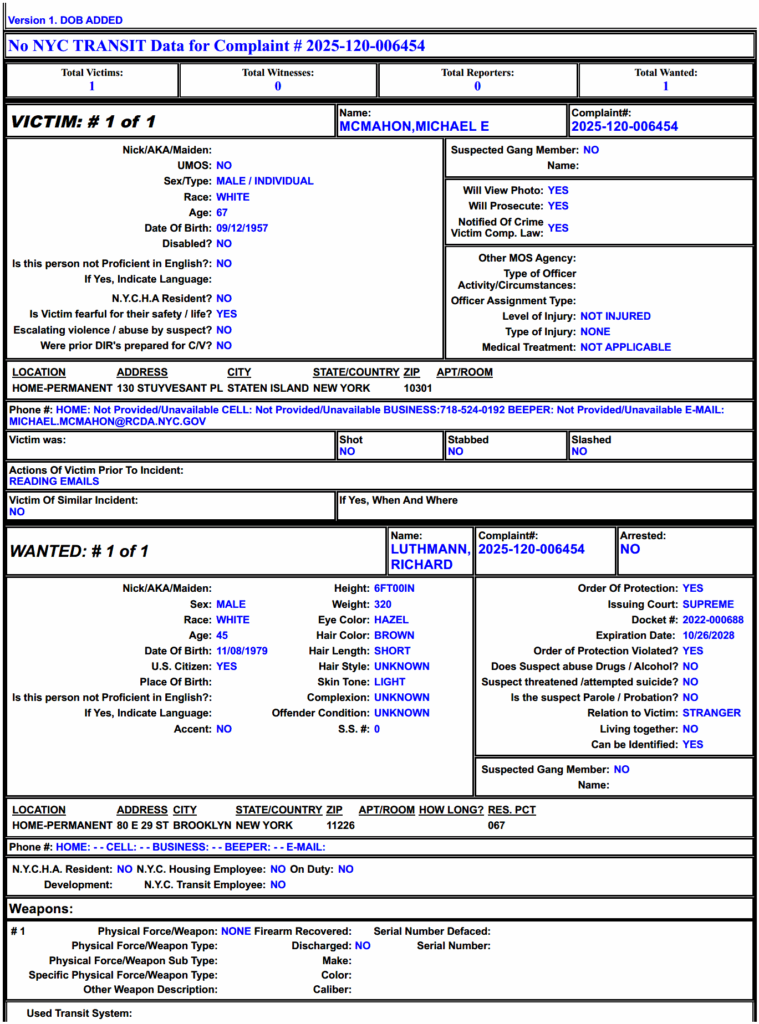

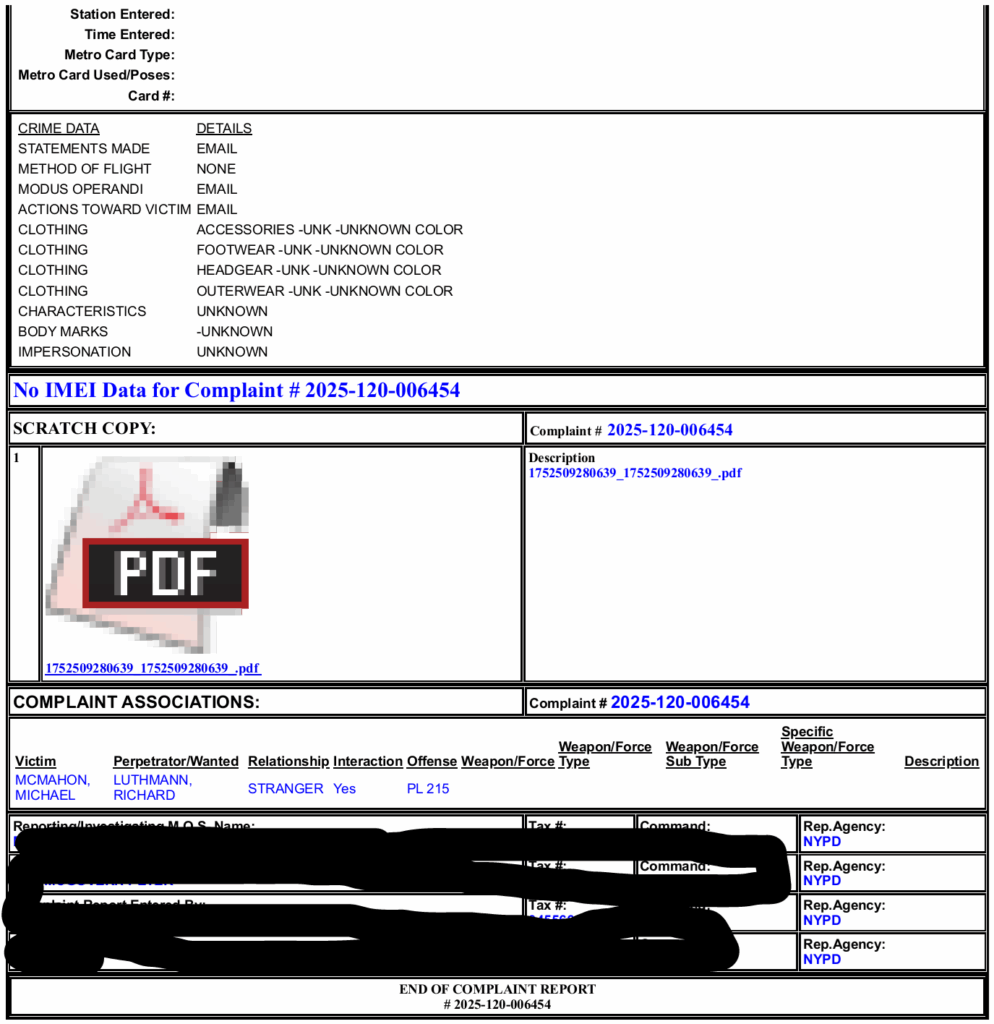

The case against Luthmann stems from a bizarre criminal complaint by DA McMahon. He claims he “feared for his life” after receiving a mass Substack email not even authored by Luthmann.

The email was sent by Substack, not Luthmann, had no threats, mentioned no names, and included a one-click unsubscribe link. Yet McMahon alleged it violated a years-old Order of Protection that Luthmann was never served with.

Rodriguez’s deep ties to the McMahons have created a firestorm.

“No reasonable person could think a judge who is a long-time friend and confidant of Mr. McMahon could remain neutral,” Luthmann wrote.

He cites Judiciary Law § 14 and the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark due process rulings in Caperton v. A.T. Massey Coal Co. and Tumey v. Ohio to argue that Judge Rodriguez’s continued involvement in the case violates both state law and federal constitutional guarantees.

Under Judiciary Law § 14, a judge must recuse when he is “interested” in the outcome. Luthmann argues that Rodriguez’s admitted and lauding 30-year personal and professional relationship with complainant District Attorney McMahon and his judge wife renders him “interested” within the meaning of the statute.

Luthmann argued that Rodriguez’s close alliance with McMahon creates a “serious, objective risk of actual bias” that falls squarely within Caperton’s test.

“Judge Rodriguez doesn’t have to hate me to be disqualified,” Luthmann wrote. “He just has to appear to be too close to the guy trying to jail me. And he does.”

The motion describes Rodriguez as “interested” and compromised.

The McMahon’s Political Vendetta

The backstory paints a picture of personal vendetta masquerading as prosecution. McMahon and Luthmann’s feud dates back to 2015. Luthmann, then a practicing attorney and political satirist, created a parody Facebook page mocking McMahon’s campaign. It was clearly labeled satire and linked directly to McMahon’s official site. Luthmann also exposed fraudulent petition signatures and supported McMahon’s opponent.

In 2017, Luthmann helped expose a backroom scheme between McMahon and his wife, then-Administrative Judge Judith McMahon. According to court clerk whistleblower Michael Pulizotto, they created a “Special Narcotics Part” to steer warrants to a prosecution-friendly judge. Luthmann released audio evidence.

The scheme was dismantled, and Judge McMahon was demoted. Luthmann says the McMahons have been out for blood ever since.

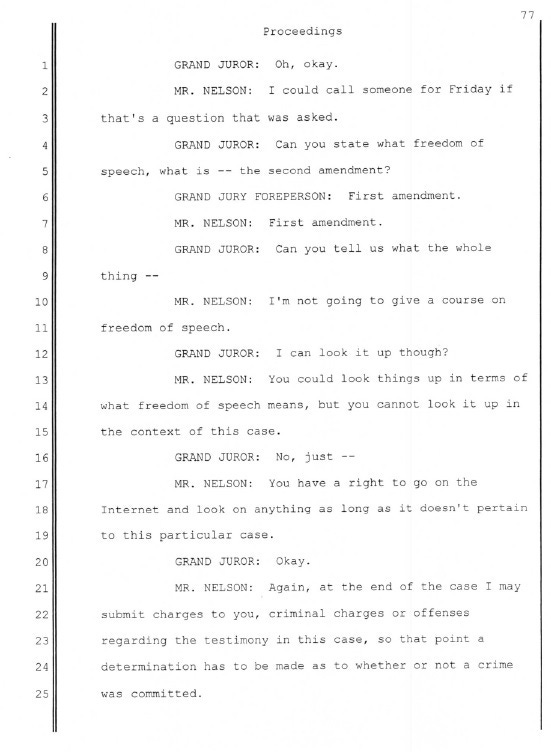

In 2018, McMahon used a special prosecutor to indict Luthmann over the 2015 Facebook satire, after the first prosecutor, Tom Tormey, declined. The grand jury was told the First Amendment was irrelevant.

The second special prosecutor, Eric Nelson, was later rewarded with city legal work.

Luthmann was also prosecuted federally. He alleges McMahon’s allies “walked in” fraudster Guy Cardinale to the feds to get him out of the way.

After serving time, Luthmann became a journalist and launched a newsletter, This Is For Real. In July 2025, that newsletter forwarded a guest column to 33,000 readers. McMahon received it at his public office email, then filed a police report claiming he feared for his safety.

Luthmann says Substack records show McMahon signed up himself and interacted with the page.

NYPD listed McMahon as “the victim,” and labeled Luthmann a “stranger”—a blatant lie, according to the motion.

“Mr. McMahon knowingly misled law enforcement by portraying me as a random unknown person,” Luthmann wrote.

A Court Rigged from the Start?

Luthmann’s motion describes a pattern of forum shopping, judicial favoritism, and systemic abuse. After Richmond County Supreme Court Justice Marina Cora Mundy recused herself in 2022, Luthmann says the case was illegally transferred to Kings County. There was no lawful change of venue, no hearing, and no consent. Administrative Judge Deborah Kaplan issued a fiat transfer.

That violated the New York Constitution, which guarantees criminal defendants the right to be tried in the county where the alleged crime occurred.

“Administrative reassignment by OCA is not a substitute for judicial authority,” Luthmann argued.

He cited People v. Ribowsky, People v. Greenberg, People v. Ahmed, and People v. Boston to show that venue, indictment procedures, and court assignments are not mere matters of convenience or administrative discretion—they are constitutional mandates central to due process.

In Ribowsky, the Court of Appeals reaffirmed that criminal defendants have a fundamental right to be tried in the county where the alleged offense occurred, absent strict statutory exceptions.

In Greenberg, the court emphasized that jurisdiction cannot be created by informal practice or implied authority—it must follow the procedures set forth in statute.

Ahmed established that any deviation from the required “mode of proceedings,” such as a judge not being present during a critical stage of trial, results in automatic reversal regardless of waiver.

And in Boston, the Court vacated a plea because the defendant waived indictment after one had already been issued—a jurisdictional defect that rendered the plea void even though the defendant appeared to consent.

Luthmann argues that the illegal transfer of his case from Richmond to Kings County, without motion, hearing, or lawful order, and the use of a defective Superior Court Information (SCI) after an indictment had allegedly already issued mirror these fatal errors. In his view, the entire case collapsed under the weight of its own procedural illegality.

“This is not technicality—it’s constitutional law,” he wrote. “If you don’t follow the law to prosecute someone, you don’t get to prosecute them at all.”

Luthmann entered a 2020 plea deal while still in federal custody. He says he was misled and that the deal was not made knowingly, voluntarily, or intelligently. The state promised resolution of the Richmond County charges, which he now argues were never lawfully prosecuted. The motion seeks vacatur of that plea as invalid under People v. Catu.

The Recusal Question

The most explosive part of the motion is the recusal demand. Luthmann accuses Judge Rodriguez of being “interested,” compromised by a long-standing alliance with the McMahon family, and incapable of impartiality. He says Rodriguez is facing reelection and has every incentive to side with McMahon.

The Rules of Judicial Conduct require judges to recuse when impartiality “might reasonably be questioned” or where there’s a personal bias. Luthmann says this isn’t a close call.

“Mr. McMahon is effectively a party,” the affidavit reads. “A reasonable observer would undoubtedly question the judge’s ability to remain impartial.”

Luthmann invoked the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. In Tumey v. Ohio, 273 U.S. 510 (1927), the Supreme Court held that it violates due process for a judge to have a direct personal or pecuniary interest in the outcome of a case.

Later, in Caperton v. A.T. Massey Coal Co., 556 U.S. 868 (2009), the Court ruled that even the appearance of bias—when a judge receives significant campaign support or has close ties to a party—can mandate recusal to preserve constitutional fairness.

Here, the friendship, appointments, and political entanglements are deeper. Rodriguez has already given McMahon’s wife court assignments. The two are part of the same Staten Island power machine.

Luthmann warns: “The integrity of the judiciary in the eyes of the public demands nothing less” than recusal.

Rodriguez now faces a stark choice: protect his political benefactors, or step aside to preserve what’s left of the court’s credibility.

If he stays, expect appeals and federal litigation. If he recuses, it may trigger a wider inquiry into how deep the McMahon judicial machine runs.