Prisons are Petri Dishes During COVID

Richard Luthmann's Latest: Compassionate Release Saves Many

This article first appeared in the Frank Report (www.frankreport.com) as:

Prisons are Petri Dishes During COVID; Compassionate Release Saves Many

By Richard Luthmann

I arrived at the Brooklyn MDC in December 2017. Three months later, I was granted bail – in March 2018. But three months later, the judge revoked my bail – in June 2018. I was back at MDC for a couple of months, then shipped to Federal Medical Center-Devens until November 2018.

I returned to MDC from Thanksgiving 2018, through 2019 and into early 2020. By the time Covid started, I was at Allenwood Low-Security Correctional Institution in White Deer, Pennsylvania.

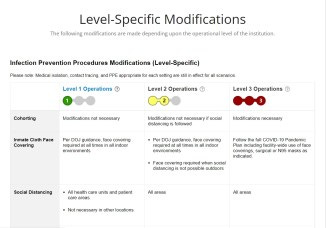

The Bureau of Prisons had an “Action Plan” called “Modified Operations,” which meant, “lock everybody down all the time.”

Bureau of Prisons guards, like many federal employees, are inclined toward laziness. Once they had the excuse to confine inmates to their cells, they ran with that inclination, magnified, amplified it, you might say.

If before COVID, prison staff did the “bare ass minimum,” you can bet you sweet ass, they had nothing to do but sit on theirs with “Modified Operations.”

Some of them, through indolence, expanded theirs. Some had ponderous asses.

Their only job was to ensure the virus wasn’t transmitted into the prison. The guards and staff were the only ones who could bring it in, and they failed.

I was in Allenwood, Pennsylvania, a low-security prison. You might think a prisoner would do better in low. With COVID-19, it’s the worst, because the low-security prisons are open-air dormitories.

Instead of having a cell where two spread germs, you have a dormitory with 120 people.

When COVID-19 hit Allenwood, everyone got it.

These prisons have been called “Petri dishes.” That’s what it is.

Usually, immunities go up because you’re exposed to so much in prison. You always have sniffles or a cold. You’re never 100%, but your immunities get better. But if you have a pandemic or contagious illness, it becomes a problem.

I got to Allenwood, and COVID-19 started.

Trump signed the First Step Act, allowing prisoners to petition for compassionate release. Once COVID-19 came, everybody put in for a compassionate release.

As a jailhouse lawyer, I drafted compassionate release motions and got a few people out. One was my cellie Samuel Walker, a black guy from Buffalo in his early 70s.

He had a long record and got jammed up because he was the driver for a pimp selling teenage girls. He was charged with low-level sex trafficking. Even low-level offenses are serious where females are underage.

Sam and I played cards, mostly pinochle. Sam told stories.

He was a prisoner during the 1971 Attica riots, a teenager then.

For years he went by an alias, “Michael Gray.” In West Virginia, Michael Gray was a black dude of means who ran nightclubs and pimped women. He had politicians, lawyers, and judges in Wheeling, “taken care of.”

In New Orleans, Michael Gray spoke with an “Islands” accent and peddled fake jewelry to rich people. In Atlanta, Michael Gray was known to make midnight runs of contraband. He hustled in Ohio, Los Angeles, New York City, and all points between.

Some of Sam’s best stories were about his hometown Buffalo. He hung with Rick James back in the day.

But now, Sam was in his 70s, and COVID-19 was trying to knock him out. He asked if I could put together a compassionate release motion for him.

I did. It was mailed on November 23, 2020, and hit the WDNY docket a week later. Sam Walker’s Compassionate Release Motion.

A little more than a month later — on January 5, 2021, Judge Lawrence J. Vilardo granted Sam’s motion. He was released to home confinement. His life, thanks to the good judge, may very likely had been saved.

Once Walker got his release, I had a line of clients around the door. Everyone wanted me to write compassionate release motions.

Walker’s Release Order issued by Judge Vilardo.

All my time was spent doing legal work for months.

In prison, they do not necessarily give a prisoner the best medical attention. But there was no forced vaccination or forced anything in BOP Medical. There is “conditioning.”

If you don’t get the vaccine, you’ll get hard treatment. You could get placed in the SHU, the Segregated Housing Unit, or other segregated housing because you don’t have the vaccine.

Nothing is “forced.” But refusal invites retaliation.

So, Sam Walker, who Judge Vilardo agreed to let out for compassionate release, got taken to the hospital. He was very sick from Covid.

What the BOP did was take everybody who tested positive to a separate unit, and quarantine everybody together. If anybody got deathly ill, they would take them to the hospital. Sam was one of those. He was quarantined with a group, got sicker, and went to the hospital in late December.

His case was life-threatening. He recovered a bit by the time the release was granted. But if another strain came through, it might have taken old Sam away.

By that time, the BOP was looking to release prisoners who were sick or in high-risk categories to cut medical costs. A lot of older inmates got out on compassionate release. They went to home confinement.

Inmates with medical complications and prisoners with AIDS got out immediately because BOP did not want to pay for Covid complications for somebody on AIDS medication. They worried about medical costs.

Compassionate Release may more aptly be called “Compassionate Cost Cutting” by the BOP.

As far as the release, the judge can release a prisoner to BOP Home Confinement on an ankle bracelet and other restrictions or end his prison term and remand him to the United States Probation.

The First Step Act’s compassionate release gave judges discretion and allowed inmates to petition courts.

For those who remained, there were masks.

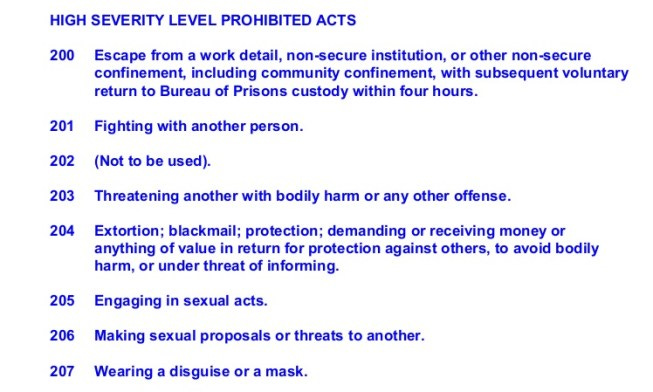

The BOP has a Program Statement detailing Prohibited Act.

Rule 207 states it is a violation to wear a mask. The BOP does not want prisoners wearing masks. They want to identify prisoners. Before Covid, wearing a mask was an offense on par with fighting, extortion, and sexual threats.

After Covid, it was a violation not to wear a mask.

As a jailhouse lawyer, it was my duty to help clients avoid punishment. When one my clients got caught not wearing a mask, I would have him go to his disciplinary hearing with a BOP rulebook and say, “It’s a violation to wear a mask, and it’s a violation not to wear a mask. So which is it?”

After that happened a couple of times, the Unit Team doing the discipline got a little frustrated. It was funny to a degree, but not too funny. Not much is funny in prison. It’s a place of secret sorrows. As the poet said, we call a man cold when really he is only sad.

A former attorney and former federal prisoner. Richard Luthmann is a writer and contributor for the Frank Report. He recently appeared on Peter Mingils and Scott Johnson’s radio show from whence some topics discussed in this post were amply discussed and enhanced by questions and comments.

About the Author

Richard Luthmann is a writer, commentator, satirist, and investigative journalist with degrees from Columbia University and the University of Miami. Once a fixture in New York City and State politics, Luthmann is a recovering attorney who lives in Southwest Florida and a proud member of the National Writers Union.

For Article Ideas, Tips, or Help: richard.luthmann@protonmail.com or call 239-287-6352.

This is Satire? is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.