Unconstitutional: DOJ Flipped Role of Grand Jury on Its Head to the Detriment of the People

Read Luthmann's Latest From the Frank Report

This article was first published in the Frank Report (www.frankreport.com) on February 23, 2023. Read it here:

Unconstitutional: DOJ Flipped Role of Grand Jury on Its Head to the Detriment of the People

The people, not the government, designed the grand jury to protect citizens against corrupt and incompetent prosecutors.

The people designed it as a shield to protect citizens from prosecutors seeking convictions without sufficient regard for the possible innocence of their targets.

While the grand jury could be a sword to enable prosecutors to indict criminals, that was not its purpose. The grand jury’s primary function is to shield citizens from unjust government prosecutions.

The grand jury’s creation was from the people who recognized that prosecutors, with their power and incessant claims of infallibility and integrity, are not above the common failings of lesser humans.

The U.S. Constitution literally bars a federal prosecutor from indicting anyone. Through the grand jury, the people must first consent to any federal indictments of any felony.

However, the U.S. Department of Justice managed, as government institutions often do, to outsmart the people. Today’s grand jury is less than a shell of what it was intended to be. It is no longer a shield for citizens—only a sword for prosecutors.

According to the U.S. Courts’ Handbook for Grand Jurors, “The grand jury operates both as a ‘sword,’ authorizing the government’s prosecution of suspected criminals, and also as a ‘shield,’ protecting citizens from unwarranted or inappropriate prosecutions.”

The Bureau of Justice Statistics shows the current balance of sword and shield. According to one study, federal grand juries returned an indictment in all but 11 of 162,000 cases the DOJ brought (.006%).

It means 99.994 percent of the time; the grand jury was a sword, and 0.006 percent, a shield.

The American people may not care about rights, duties, or powers when they sit on a grand jury. The average citizen believes perhaps that they are under the direction of prosecutors and serve as their assistants to rubber stamp their career goals.

The Court’s Handbook says, “The purpose of the grand jury is not to determine guilt or innocence, but whether there is probable cause to believe that a crime was committed and that a specific person or persons committed it.”

The grand jury alone may charge a citizen, not prosecutors. Over time, the DOJ coopted the grand jury and turned it into their witless and unconstitutional tool.

The handbook continues, “If the grand jury, after appropriate investigation, finds probable cause exists against a person suspected of having committed the crime, then it will return a written statement of the charges called an ‘indictment.'”

If they don’t find probable cause, they decline to indict, which grand juries did in 11 cases out of 162,000.

Because Americans are unaware of their constitutional duty, grand jurors do not do appropriate investigations and accept whatever a prosecutor says, indicting whoever pleases the prosecutor to indict—at least 161,989 times out of 162,000.

The reason for plea deals is not hard to understand. There is a trial penalty. If a defendant proceeds to trial and loses, they will be punished severely. The judge is forced to give the Defendant more prison time, even though there is a “constitutional right” to a jury trial. This leads to indicted citizens taking a plea deal 97 percent of the time.

With the disappearance of the informed grand jury, combined with the uninformed trial juries, came a shifting of rules for trials in federal cases that greatly favored the prosecution. On top of that, because neither Americans nor their elected representatives investigate or engage in meaningful oversight, the DOJ gets away with overcharging citizens. This virtually coerces subsequent plea deals since most targeted citizens will not risk draconian prison sentences with uniformed trial juries making decisions.

Federal trials have practically disappeared. Few defendants want to risk years, sometimes decades, in prison when they can take a plea deal and limit their exposure to prison time, even if they are innocent.

One thing is missing by today’s grand jury, which, if restored, would return this constitutional right to the people.

According to the U.S. Courts; “Handbook for Grand Jurors, “The federal grand jury’s function is to determine whether the person being investigated by the government shall be tried for a serious federal crime alleged to have been committed within the district where it sits. Matters may be brought to its attention in three ways: (1) by the government attorney; (2) by the court that impaneled it; and (3) from the personal knowledge of a member of the grand jury or from matters properly brought to a member’s personal attention.”

Number #3 is something prosecutors do not want grand jurors to know. If they did, it would make their jobs far more difficult.

Number #3 is that a grand juror can investigate based on their “personal knowledge of matters brought” to their attention, which includes matters the grand jurors summon for their attention. Only the grand jury can summon witnesses to the grand jury and documents.

The current practice is for prosecutors to dictate who they want to call and get the grand jury to sign off. But the grand jury neither has to consent to the prosecution’s witnesses nor be limited to witnesses the prosecution wants to call. The grand jury is not dependent on the prosecutor alone for information or the direction they seek to take an investigation. It can go anywhere it likes. Once information is brought to a grand juror’s attention, even through witnesses the government calls, the grand jury can explore and seek to investigate further and make their own decisions as to whom to call.

Yet, in practice, we know it is not so in 161,989 of 162,000 cases.

So the grand juror handbook is couched in absolutes and indefinite. The one absolute is #3, “The grand jury may consider additional matters otherwise brought to its attention.” That means anything, including calling witnesses or investigating matters pointing to innocence. The courts have to say this because it is in the U.S. Constitution. But they do not want this.

It is not enough to listen to the government attorney alone. The government attorney is only concerned with presenting information that points to guilt. No matter how improbable, there’s always the chance that a target is innocent. The grand jury, as a constitutional obligation, needs to look further and deeper.

It is only fair. What DOJ prosecutors, as humans with power, don’t care much about is that a federal indictment ruins the citizen. It is punishment before trial. It devastates almost anyone. This is the true purpose of the grand jury- to prevent that possibly innocent citizen from having his life ruined by prosecutors who only advance in their careers by indicting people.

The grand jury “should,” as the handbook says, but is certainly not compelled to “consult with the government attorney or the court before undertaking a formal investigation of such matters.”

But implicit in this is that after consulting with the government attorney, they are not bound to follow the prosecutors’ advice. They are free to ignore it. They cannot be punished if, in good conscience, they wish to investigate matters on their own.

The DOJ does not want you to know that, lest it blunts the sword and strengthens the shield. The last thing the Department of Justice wants is for the grand jury to return to being a shield.

It is understandable since this is the reason for a grand jury to be a check on prosecutors, so why on earth would any one of them ever want to be checked? They might be honest, or maybe not, but they do not want the people checking their power. That is why the Founding Fathers put grand juries in the Bill of Rights.

Government prosecutors naturally want conviction stats over pure justice. There are not enough criminals to fill all the prisons. The grand jury, not being incentivized to indict, wants justice over conviction stats, as it is seen that a group of random Americans without a motive to indict will prefer justice and fairness.

The oath taken by the grand jurors “binds them to inquire diligently and objectively into all federal crimes committed within the district about which they have or may obtain evidence, and to conduct such inquiry without malice, fear, ill will, or other emotion.”

It requires them not to be the prosecutor’s tool.

The grand jury calls witnesses. It is not obliged to call only witnesses the government wants them to call. They are not required to let the government attorney ask all the questions of witnesses. All members of the grand jury may question witnesses. And should do so. And if that leads them in a direction the prosecutors do not want them to go, the grand jury has a duty under the Constitution to be independent. Grand jurors cannot be punished if they disagree with government prosecutors. They are supposed to disagree when appropriate. That’s what the Founding Fathers intended.

During their investigation, the grand jury can dismiss the prosecution at any time and discuss things by itself.

The grand jury deliberates without the prosecution. The prosecution cannot be present.

But the way the present system works, the prosecutor doesn’t need to be present in 161,989 cases out of 162,000.

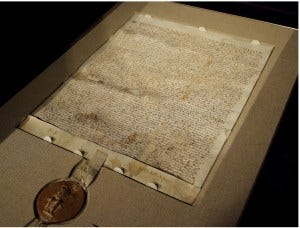

History of the Grand Jury

In his Commentaries on the Laws of England, Sir William Blackstone wrote, “so tender is the law of England of the lives of the subjects, that no man can be convicted at the suit of the king of any capital offence, unless by the unanimous voice of twenty-four of his equals and neighbours.”

He meant the grand jury. But not the American grand jury today.

By 1635, the Massachusetts Bay Colony instituted its first grand jury, making grand juries far older than most American institutions. A century later, in colonial times, the British government made plenty of presentments. Still, grand juries often refused to indict on alleged violations of the Townshend and Stamp Acts, of sedition, such as when a publisher criticized British government officials, and non-political crimes like horse thievery, grand larceny, burglary, or murder.

These grand jury acquittals followed the tradition of English grand juries pushing back against government charges. Not everyone the prosecution seeks to indict is guilty, the grand jury said.

The American Grand Jury

The first clause of the Fifth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, part of the Bill of Rights, has a grand jury clause.

The Bill of Rights is not concerned with enhancing the power of the government over the people or creating tools for the prosecution. It is concerned with declaring the people’s rights against the government. The Bill of Rights should be interpreted as enumerating essential freedom principles as rights that the Founding Fathers felt needed to memorialize for a future when the purpose of those rights might be forgotten.

The Grand Jury Clause guarantees that “No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury.”

The U.S. Supreme Court defined infamous crimes as any crime where the punishment can be more than a year in prison. i.e., a felony.

“Grand juries are the constitutional inquisitors and informers of the country; they are scattered everywhere, see everything, see it while they suppose themselves mere private persons and not with the prejudiced eye of a permanent and systematic spy. Their information is on oath, is public; it is in the vicinage of the party charged and can be at once refuted. These officers, taken only occasionally from among the people, are familiar to them, the office respected, and the experience of centuries has shown that it is safely entrusted with our character, property, and liberty.” –Thomas Jefferson to Edmund Randolph, 1793. M.E. 9:83.

The Bill of Rights did not include the grand jury clause for grand jurors to serve as tools for prosecutors.

Of the founding 13 states, 11 contained guarantees for grand juries in their original state constitutions or declarations of rights. From 1792 to 1844, 13 more states protected citizens through the guarantee of a grand jury so that the state prosecutors did not have the power to indict anyone for a felony without the people’s permission.

The Decline of the Grand Jury

Around the middle of the 19th century, there was a movement to abolish or weaken grand juries. The movement went hand-in-hand with attacks on citizen participation in the courts, as pro-government authority advocates often supported by newspapers questioned the intelligence of juries, highlighting cases of injustice, [as if there were none by prosecutors] spreading rumors of drunk or corrupt jurors, and opining that jury power was out of control.

They had no foresight that the purpose of the grand and petit [trial] jury is to prevent the government from going out of control.

The New York Herald criticized weak-minded juries for being too sympathetic to criminals for not indicting or acquitting certain defendants [instead of attributing the acquittals to a lack of evidence].

The Democratic Review argued that jurors should no longer be made up of the common people of America but exclusively of lawyers.

The New York Times advocated for a majority vote of juries rather than the time-honored safeguard of liberty – the unanimous jury verdict.

These pro-government, anti-constitutional stories prompted calls for juries to be reined in or eliminated.

The courts and prosecutors supported this and regularly failed to inform grand jurors of their true obligations.

Leave it to the professionals, is what they said in effect.

It influenced America in subtle ways.

Knowing that the people are not involved in protecting each other from professional prosecutors, lawmakers became susceptible to lobbyists interested in putting more people in prison. Or making the jobs of the professional class of employees involved in the criminal justice system easier and more profitable.

The grand jury’s decline came as the “professional government” class rose and federal laws became more complex. And more people were sent to prison.

Comeback?

Can the grand jury return to serve its historic role as a sword and shield to both indict criminals and protect the targeted citizen from an overzealous prosecutor?

Once an individual is indicted, they are almost always sunk reputationally, financially, and psychologically.

The naive children of the 21st century seem to think that whatever their governors tell them about their own integrity is true and that power ennobles and does not corrupt.

For most, the powers and protections of the grand jury are a legal fiction, and this once-venerable institution serves as a prosecutorial rubber stamp. As former New York State Chief Judge Sol Wachtler famously said, “The government can indict a ham sandwich.”

Today, the government’s reach is all-encompassing. But tomorrow, when informed jurors enter the grand jury, they can insist that, as the DOJ says on its website, they be independent of the government attorney.

The DOJ’s policy on grand juries states:

In dealing with the grand jury, the prosecutor must always conduct himself or herself as an officer of the court whose function is to ensure that justice is done and that guilt shall not escape nor innocence suffer. The prosecutor must recognize that the grand jury is an independent body, whose functions include not only the investigation of crime and the initiation of criminal prosecution but also the protection of the citizenry from unfounded criminal charges. The prosecutor’s responsibility is to advise the grand jury on the law and to present evidence for its consideration. In discharging these responsibilities, the prosecutor must be scrupulously fair to all witnesses and must do nothing to inflame or otherwise improperly influence the grand jurors. [updated January 2020]

This makes for excellent legal fiction, but tomorrow art could imitate life, and fiction could cease. If grand jurors know their role, they can refuse to allow prosecutors to overcharge citizens and act like investigators. The Founding Fathers felt this was essential to preserve liberty, which means controlling government.

According to the U.S. Constitution, grand jury members must demand independence from government prosecutions. To not be independent is betraying the Constitution.

There may soon be a different ratio than 11,989 uses of the sword and 11 instances of the shield.

Richard Luthmann is a writer, commentator, satirist, and investigative journalist with degrees from Columbia University and the University of Miami. Once a fixture in New York City and State politics, Luthmann is a recovering attorney who lives in Southwest Florida and a proud member of the National Writers Union.

Drop me a line if you are a victim of the “Swamp” of corrupt politicians, lawyers, judges, or courts. I write about criminal justice, courts, prisons, and reform.

"Nihil est incertius vulgo, nihil obscurius voluntate hominum, nihil fallacius ratione tota comitiorum.” (Nothing is more unpredictable than the mob, nothing more obscure than public opinion, nothing more deceptive than the whole political system.)

~ Marcus Tullius Cicero

For Article Ideas, Tips, or Help: richard.luthmann@protonmail.com or call 239-287-6352.

The news media is a critical check on the powerful, serving as a watchdog to hold elected officials and other public figures accountable for their actions. The media was first called the fourth estate in 1821 by Edmund Burke, who wanted to point out the power of the press. The press plays a crucial role in providing citizens with access to information about what is happening in government, as well as shining a light on corruption, abuse of power, and other forms of wrongdoing.