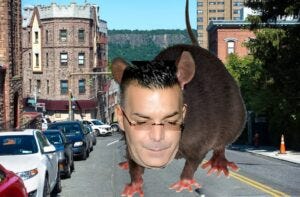

Federal Rats Rewarded: New Fed Sentencing Rules Suck Up to Snitches

Sentencing Commission guts guidelines, leaving only “snitch” deals and a safety valve for relief. Critics say the shake-up empowers “maniac” judges and erodes trust in an already shaky system.

NOTE: This piece first appeared on NYNewsPress.com.

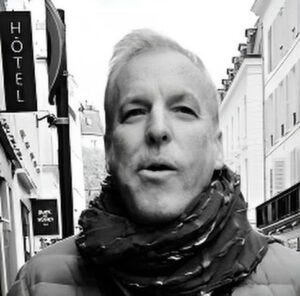

By Dick LaFontaine with Richard Luthmann

Only Snitches Get Breaks Under New Guidelines

If you want a break in federal sentencing now, you’d better be a rat. In a sweeping overhaul set to take effect November 1, 2025, the U.S. Sentencing Commission has axed nearly all guideline “departure” leniency provisions – except those reserved for snitches.

Gone are most of the old loopholes that let judges soften sentences for things like minor roles or family hardship. The only remaining formal departures are for “substantial assistance” to authorities (Guideline §5K1.1) – basically turning informant – and for certain “early disposition” or “fast-track” programs in select districts.

In other words, the last escape hatches favor rats.

Aside from these, a defendant’s lone hope for mercy is the so-called “safety valve,” a 1994 law allowing first-time, nonviolent drug offenders to avoid mandatory minimums if they spill all the beans about their crime. Officials insist this prison “debriefing” isn’t technically snitching, but many inmates see it exactly that way.

Critics charge the Sentencing Commission “loves snitches.” They note that by scrapping other avenues for leniency – yet keeping the rat rewards intact – the Commission has sent a loud message about its priorities.

Historically, nearly one in five federal defendants got a sentence reduction for turning state’s evidence. Most downward departures were already coming from government-backed cooperation deals or fast-track programs, underscoring how the system has long favored those who help prosecutors.

Now that bias is codified outright. If a defendant won’t sing for the feds, they can forget about any guideline-sanctioned break. No more mercy for keeping quiet – only those who play ball with the government get the payoff.

It’s a development one defense lawyer summed up bluntly: “Snitches get riches, and everyone else gets prison time.”

Federal Rats Rewarded: Judges Unbound, Sentences All Over the Map

The Sentencing Commission touts this overhaul as “modernization” – a streamlining of the process to reflect how courts sentence in practice. Under the updated guidelines, judges will “no longer consider departures” based on any specific criteria.

Instead, once the offense level and criminal history are calculated, the court skips straight to the broad statutory factors in 18 U.S.C. § 3553(a) – issuing whatever sentence they deem “sufficient, but not greater than necessary.”

In Commission-speak, they replaced the patchwork of departure rules with a “more structured approach to variances” grounded in the judge’s discretion.

The goal, they claim, is greater uniformity and simplicity. Eliminate the rarely used departure technicalities, the reasoning goes, and focus on one big question: what does justice require for this defendant? The Commission even asserts that dropping departures will “reduce disparities” and make sentencing more consistent overall.

But many in the trenches foresee the opposite – a Wild West of judicial whimsy. By throwing out calibrated departure guidelines (except the snitch clause), the Commission has effectively unleashed 700+ federal judges to go rogue.

“Maniac judges” now have free rein, critics warn, to impose whatever punishment fits their personal philosophy. One judge might be a hanging judge who never met a mitigation he liked; another might be a softie moved by every sob story. With departures gone, there are no guide rails on how much weight to give factors like a defendant’s age, family ties, or minor role.

Some judges will still vary downward for those reasons – others may flat-out refuse.

The result?

“Sentences for the same crime will be all over the map,” says one former federal inmate observer, “depending on which judge you draw.”

This is precisely the scenario the original 1987 Sentencing Guidelines aimed to prevent. Back then, wildly uneven sentences from courtroom to courtroom had eroded public faith in justice. Now that uniformity is unraveling.

As one exasperated attorney put it, “We’re back to luck-of-the-draw sentencing. Justice by geography and judge temperament.”

The Commission insists appellate courts will rein in extreme outliers, but skeptics aren’t buying it. They see an advisory guideline scheme with even less actual guidance – a recipe for disparity under the banner of “flexibility.”

Federal Rats Rewarded: Confidence at Rock Bottom as Uniformity Vanishes

These changes drop into a justice system already mired in distrust. Americans’ confidence in the courts has been declining for years – hitting a record low of 35% last year, according to Gallup. Great job, Sentencing Commission: as if public faith wasn’t low enough, critics say, this move throws another log on the fire.

“The entire DOJ is broken,” blasts Richard Luthmann, a former New York lawyer-turned federal prisoner-turned journalist on prosecutorial abuse. “They should just be honest and rename it the Department of Prosecution or Persecution, depending on the day and the case.”

He also says that the new rules will send more rats to the prison morgue.

“There are judges who throw Star Wars numbers out there and, in part, create the monsters that they sentence. If you’re sitting in jail for the next thirty years and probably won’t see the light of day, what’s stopping you from hatching a plan to kill the rat in your case?” Luthmann said. “The Bureau of Prisons likes to hide a lot of things. They can’t hide the bodies in the morgues.”

Moreover, Luthmann and others argue that for the past quarter-century, federal prosecutors haven’t just targeted crimes – they’ve targeted groups of people. From sweeping drug conspiracy crackdowns to post-9/11 terrorism stings, the feds made a habit of casting wide nets and flipping insiders.

The perception on the street has been that justice is a rigged game: snitches and cooperators prosper, while those who won’t (or can’t) sell out someone else get the book thrown at them. Now, by formalizing “snitch-only” leniency and leaving everything else to judge roulette, the Commission may have confirmed the public’s worst suspicions.

Even some who support sentencing reform are uneasy. Uniform sentencing was supposed to ensure that like cases are treated alike. But without clear guidelines for departures, one defendant’s outcome might hinge on which judge they face and how that judge feels about, say, an addict’s rehab effort or a grandmother’s plea for mercy.

Such disparities – whether real or perceived – feed a narrative of injustice at a moment when trust in the system is fragile.

“This is how you lose whatever confidence people have left,” one long-time defense attorney said. “When Joe, in one courtroom, walks for the same crime that sends Jack, in another courtroom, away for 20 years, people throw up their hands. They think it’s all arbitrary – and they’re not wrong.”

Indeed, the Sentencing Commission’s own rhetoric about enhancing fairness rings hollow to its harshest critics. They see a cynical pattern: first, decades of one-size-fits-all punishment aimed at entire categories of offenders, and now a lurch to free-form discretion that could magnify disparities.

In the end, the only consistent thing may be the inconsistency. As judges chart their own courses and only the rats get rewarded, many are bracing for a new era of sentencing chaos – and a further collapse in confidence that justice will be equally served.