MAKE PRIVATEERING GREAT AGAIN

A Return to Privateering – A Strategic Concept for Unconventional Warfare

NOTE: This article was first published in Strategy Central. Republished with permission from the author, Jeremiah Monk.

By Jeremiah Monk

“[The Congress shall have Power . . . ] To declare War, grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal, and make Rules concerning Captures on Land and Water; . . .”

U.S. Constitution, Article I § 8, clause 11[i]

INTRODUCTION

An often overlooked clause in Article I of the US Constitution grants Congress the War Power authority to issue “Letters of Marque,” official documents issued by a sovereign nation authorizing private citizens, often ship captains, to capture enemy vessels and goods. This was a practice particularly prevalent during the 18th and early 19th centuries, and at the time of the Founding Fathers of the United States was a fairly common instrument of national power.[ii]

The strategic application of privateering effectively ended in the mid-19th century. Treaties largely banned the practice, and the conduct and character of warfare from that point on rendered privateering unnecessary. But to this day, the US retains the right to issue Letters of Marque. This capability offers not only a potent strategic deterrent but also a significant strategic option for the nation to leverage in the event of a war with China.

PRIVATEERING AGAINST THE BRITISH

At the time of America’s founding, the small U.S. Navy faced a dilemma: how to combat an adversary with a much larger naval fleet but who offered a strategic vulnerability in its reliance on maritime trade and resupply. The strategy employed was effectively outsourcing, granting private vessels the authority to interdict British supply shipments.

Issuance of Letters of Marque was a common practice employed by European powers since the Middle Ages. So effective was the strategy that at the time of the Revolution, the Founding Fathers wove it into the Constitutional fabric of the United States as a means to bolster the fledgling nation’s small Naval force. Congress exercised this authority against British shipping during both the American Revolutionary War and the War of 1812. In the War of 1812, American privateers captured between 1,200 and 2,000 British vessels, making for a profound strategic impact on the conflict.[iii]

The capture of British merchant ships severely disrupted trade, straining British resources and diverting the Royal Navy’s attention from other military operations. England was forced to allocate more ships and resources to protect their merchant fleet, which could have otherwise been used in direct military engagements against the United States. The success of American privateers simultaneously boosted morale on the home front, demonstrated the effectiveness of privateering as a form of asymmetric warfare, and helped garner support for the war effort among American citizens.

Ultimately, the economic pressure exerted by privateering contributed to the British decision to negotiate peace, leading to the Treaty of Ghent in 1814. The disruption of trade and the financial losses incurred by British merchants created a constituency within Britain that pushed for an end to the war. The strategic impact of privateering during the War of 1812 extended beyond the immediate capture of ships. It played a crucial role in economic warfare, resource allocation, morale, and ultimately, the diplomatic resolution of the conflict.

AN END TO PRIVATEERING?

The 1856 Declaration of Paris was a significant international agreement aimed at regulating maritime warfare.[iv] It established key principles, including the abolition of privateering, the protection of neutral goods (except contraband) under an enemy’s flag, and the requirement that blockades be effective to be legally binding.

The United States did not sign the Declaration of Paris, primarily to preserve the U.S. government’s ability to leverage a practice that had been so valuable during the American Revolutionary War and the War of 1812. The U.S. viewed privateering as a means to supplement its relatively small navy and exert economic pressure on adversaries.

Today, the U.S. adheres to the principles of the Declaration and champions the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), a comprehensive international treaty signed in 1982 that establishes the legal framework for maritime activities.[v] The U.S. has also maintained and operated the most powerful Navy in the world since World War II, rendering the practice of privateering unnecessary.

However, the U.S. never signed on to the Declaration of Paris. Nor has it signed on to UNCLOS, partially due to concerns over accepting limits to its sovereignty despite having played a significant role in helping to develop it. To this day, privateering remains a dormant but legal tool of U.S. national power.

THE STRATEGIC IMPACT OF INTERDICTION

The strategy of attacking civilian maritime shipping is alive and flourishing in the modern age. In the Gulf of Aden, Somali-based raiders and Iranian-backed Houthis from Yemen are effectively leveraging the practice as a potent unconventional warfare tool. The practice presents significant strategic implications for international shipping, affecting both regional security and global trade dynamics.

The difference between piracy and privateering is nuanced, effectively coming down to state sponsorship: Piracy is an illegal act of robbery by individuals, while privateering is a tool of warfare used by the state. In the Gulf of Aden, Somali raiders operate in clear violation of international law as pirates.

The Houthis, however, attack merchant shipping in the Bab el-Mandeb Strait with the backing of the Iranian state.[vi] That they use helicopters and missiles to attack and seize ships is irrelevant – they do so at the behest of a nation that sees itself at war and, like so many of the adversaries of the West, does bother with troublesome policy distinctions that artificially categorize war as being either “irregular” or “unconventional.” By every definition, Houthi seizures can be considered acts of privateering and are having a dramatic effect:

Economic Costs:

Increased Shipping Costs: Shipping companies incur higher insurance premiums and security costs to protect vessels from pirate attacks. These additional expenses are often passed on to consumers, raising the cost of goods.

Rerouting: Some ships choose to avoid the Gulf of Aden altogether, opting for longer routes around the Cape of Good Hope, which increases fuel consumption and transit times.

Security Measures:

Naval Patrols: The presence of international naval forces, including the Chinese PLAN’s anti-piracy missions, underscores the strategic importance of securing this vital maritime corridor. These patrols aim to deter piracy and ensure the safe passage of commercial vessels.

Private Security: Many shipping companies employ private security teams to safeguard their vessels, reflecting the persistent threat of piracy in the region.

International Cooperation:

Multinational Task Forces: The threat of piracy has led to unprecedented levels of international cooperation, with countries forming coalitions to patrol the waters and share intelligence. This collaboration enhances maritime security and fosters diplomatic relations.

Impact on Regional Stability:

Economic Disruption: Piracy disrupts local economies by threatening fishing and trade, which can exacerbate poverty and instability in coastal communities.

Counterterrorism: The nexus between piracy and terrorism is a concern, as revenues from piracy can potentially fund terrorist activities, further destabilizing the region.

For the Iranians, these effects equate to a delightful return on a very small investment. By using a proxy force to put all civilian shipping through a strategic chokepoint at risk, the Iranians are achieving global economic and security impacts while maintaining a (thin) veil of deniability.

REIMAGINING OF UNCONVENTIONAL WARFARE

The U.S. military defines unconventional warfare as “activities conducted to enable a resistance movement or insurgency to coerce, disrupt, or overthrow a government or occupying power by operating through or with an underground, auxiliary, and guerrilla force in a denied area.” [vii] It is worth noting that the Iranians most likely do not concern themselves with this distinction between conventional and unconventional warfare. Regardless, as unconventional warfare is defined as the use of proxy forces to disrupt a hostile government, then privateering can arguably be considered a form of unconventional warfare exercised by a maritime insurgent force.

But what matters more than academic characterizations are the strategic effects thereof. Maritime interdiction of shipping, regardless of conventional or unconventional means, can be an extremely effective strategy, capable of bringing a superpower to its knees. The strategy of blockade, effectively the maritime version of siege warfare, can be effective but requires a large naval force. [viii] An interdiction strategy is best employed when supplies must transit chokepoints and achieve a similar effect as a blockade but for significantly less cost, force size, and risk. As exemplified by the recent accomplishments of the Houthi raiders, leveraging a proxy force to do the dirty work of attacking and seizing merchant shipping can offer enormous strategic advantages.

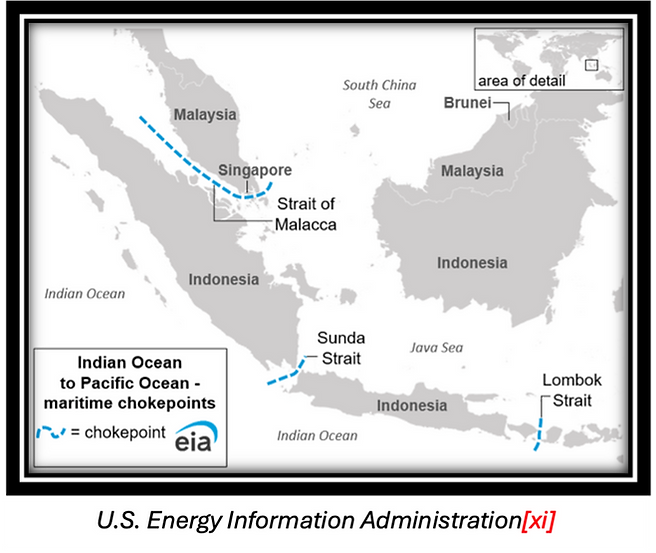

THE CHINESE ACHILLES HEEL

$3.5 trillion of shipping travels through the Strait of Malacca annually aboard approximately 94,000 ships.[ix], [x] On these vessels travel 30% of all globally traded goods and 23.7 million barrels of oil per day (in 2023). Two-thirds of China’s maritime trade volume must transit the Strait, along with 97% of its seaborne crude oil imports.[xi], [xii] Around 10% of that amount comes from Iran and another 7% from Russia. Dark Fleet[xiii] passage makes up an additional sizable but unknown portion of Chinese imports, driven by recent international sanctions on oil exports from these two countries. To say shipping through the Strait of Malacca presents a strategic vulnerability for China is an understatement of existential proportion.[xiv]

MAKE PRIVATEERING GREAT AGAIN

The opportunity here should be fairly obvious. If the United States requires a point of leverage over China, the Strait of Malacca presents a prime option. Should U.S.-China relations deteriorate so far as to result in open conflict, shipping destined for China will certainly be considered a vulnerable strategic center of gravity.

The question is the how. Interdicting merchant shipping through the Strait is not an optimal task to give to the U.S. Navy Pacific fleet, which numbers about 200 ships.[xv] In a shooting war with China, the majority of those ships will be deployed to support combat operations elsewhere, most likely either offensively against the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) and in defense of Taiwan, Japan, Korea, the Philippines, and the U.S. equities and installations in the theater.

The U.S. Navy would not be able to reallocate a sizable portion of its fleet to an interdiction mission nor accept the risk to force of operating in such confined waters. This is especially true as of those 200 U.S. ships, there is a reasonable expectation a significant portion will be removed from action in the opening days of a shooting war with China. Nor would it be good politically for the U.S. Navy, champion of navigational freedom, to be seen openly seizing civilian ships with gray-hull destroyers.

Strategically, this presents the U.S. Navy with the same challenge the Founding Fathers faced – how to attack the enemy’s strategic vulnerability of maritime shipping with a constrained naval force. The answer at the time of America’s founding was for Congress to outsource privateers via Letters of Marque. The same holds true today. The strategy of privateering offers the U.S. significant leverage over the most critical chokepoint in China’s Belt and Road, which in turn would put the Chinese economy, energy supply, and war production capacity at risk, all while preserving and protecting the U.S. Pacific Fleet’s ability to maximize the application of its combat power.

PRIVATEERING IN TOTAL DETERRENCE

The privateering strategy offers an intriguing and inexpensive option to expand U.S. Naval power through asymmetric means to hold Chinese supply routes at risk in wartime. In addition to providing an additional strategic option in wartime, the act of building such a capability before the outbreak of hostilities serves as a potent deterrent as well. Effective deterrent strategies do not seek to apply force against points of enemy strength but rather to points of vulnerability. It is not the fear of opposing strength that dissuades, it is the calculation of unacceptable repercussions. If an actor feels adequately defended against their adversary’s strength, the deterrent value of that strength is significantly diminished. Similarly, the more time an actor is given to prepare against a static deterrent capability, the less effective that deterrent will be as the actor finds ways to mitigate it.

This is where asymmetric deterrent strategies can prove so valuable. Asymmetric strategies offer a means to exploit an adversary’s specific weaknesses and vulnerabilities in cost-effective and flexible ways. They leverage flexible, targeted impacts to create significant psychological uncertainty and deterrence through unpredictability, complicating the adversary’s strategic calculations and stretching an adversary’s resources and attention. By avoiding direct, large-scale confrontations, asymmetric approaches minimize the risk of escalation and enable controlled engagement, which is crucial in maintaining stability while also preserving the more symmetric force.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff’s Concept for Competing advocates “expanding the competition into new areas will also deter adversaries, potentially forcing them to divert scarce resources away from more threatening areas.”[xvi] Therefore, the Joint Staff seems aligned with the benefits offered by a strategy that proposes to create such a strategic dilemma for the Chinese.

Any campaign that seeks to interdict Chinese maritime trade through the Bay of Bengal, Andaman Sea, and the Strait of Malacca would force the PLAN to reallocate a large percentage of their available naval force to escort duty, effectively eliminating that force from supporting combat operations. This reallocation would have the additional benefit of decreasing the force strength that the U.S. Navy would have to contend with. As Sun Tzu said of the wise commander: “Appear at points which the enemy must hasten to defend; march swiftly to places where you are not expected.”[xvii]

The Chinese are keenly aware of the Strait of Malacca’s vulnerability. They are taking steps to mitigate the risk by establishing naval bases in Cambodia and the South China Sea[xviii] and investing in a proposed 90-km land bridge across the Thai peninsula.[xix] These measures will take decades to complete. In the meantime, a campaign to establish a low-cost maritime interdiction force to hold Chinese supply chains at risk could take only a few years.

HOW TO BUILD A PRIVATEER ARMADA

Unlike in the Age of Sail, the United States does not have an available source of experienced and capable mariners to whom Letters of Marque could be issued. Such a capability must be built preemptively and deliberately. Should war break out with China, it will be too late to develop a low-cost asymmetric capability to hold Chinese shipping through the Strait at risk. Such a lucrative and cost-effective strategic option will be forfeited.

Civilian and paramilitary mariners from the Philippines, Indonesia, Brunei, Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, Malaysia, Myanmar, and Bangladesh are potential candidates for recruitment. Not all these nations will permit preemptive training of privateers on their shores. Should the time come, the US could consider leveraging a direct and localized communication campaign advertising a willingness to pay maritime bounties. For those nations that would support hosting a privateer force, U.S. Special Operations Forces are ideally suited to lead the training.

By U.S. Code, U.S. Special Operations Command is tasked with conducting unconventional warfare activities, and the command was built in part for this specific purpose.[xx] U.S. Special Operations Forces also have well-established and extensive training relationships with many of these partner nations. However, the skills provided in these training programs are largely carried over from decades past that prioritized counter-terror and direct-action tactics. In a war with China, these skill sets will prove to be of limited use for U.S. partner forces. U.S. Special Operations Command should modernize the training programs provided for U.S. allies and partners, particularly those in the Indo-Pacific region. The skills U.S. trainers provide to those nations should support and align with a larger unconventional warfighting strategy employable in both great power competition and great power warfighting.

One of the more pressing changes Special Operations Command should make to these programs should be to prioritize tactical maritime interdiction and seizure training. Special Operations trainers should help partner nations develop not only military capabilities but also help build reserve fleets of private paramilitary mariners. In a time of war, these reserve fleets could be leveraged by U.S. partners to augment host nation maritime logistics, transport, and enforcement capabilities. They can also serve as privateers in waiting, signaling to Chinese decision-makers the existence of a credible asymmetric threat that requires only a letter of authorization from the U.S. Congress to wreak havoc on the entire Chinese economic system.

CONCLUSION

Privateering is a dormant capability enshrined in the U.S. Constitution for a reason. It is a highly effective asymmetric strategy that can be leveraged to hold an adversary’s critical maritime trade routes at risk while simultaneously preserving and protecting U.S. naval power. The U.S. leveraged privateers to great effect in the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812. It should consider doing so again in contingency planning for a war with China. Maritime shipping through the Strait of Malacca presents a lucrative strategic vulnerability to the Chinese economy. It also presents a deterrent option that should not be ignored.

Training a regional private maritime interdiction capability requires relatively little investment, a mere fraction of the $120 billion cost to build and maintain a single aircraft carrier.[xxi] But building such a force does require time, strategic foresight, and a deliberate investment of training resources.

In this case, time is the critical factor. One tenant of Special Operations is that they cannot be created after emergencies occur. Without preemptive action, the U.S. will lose both this deterrent leverage and the asymmetric warfighting option. U.S. Special Operations Forces are well-suited and well-positioned to build this capability. They already possess all the necessary resources, authority, relationships, and capabilities. But those available assets must be redirected to better use to build asymmetric, irregular, and unconventional capabilities that are useful for the road ahead, not the road behind.

A war with China would inevitably be global and cross-domain, spanning trade markets, space access, civilian infrastructure, and cyber systems. Just as the U.S. experienced in the Atlantic in the last total war, maritime shipping in a war with China would again present a lucrative target. The U.S., therefore, has three strategic options with how to affect enemy maritime supply routes: ignore it, try to regular naval forces, or find ways to outsource. A privateering strategy may sound comical up front, but when analyzed, offers a very serious option that policymakers and planners should consider as the U.S. prepares to fight and deter as an underdog in a war with China.

NOTES

[i] United States Constitution, Article I § 8, clause 11. https://constitution.congress.gov/browse/article-1/#I_S8_C3

[ii] James Madison, “No. 41: General view of the powers proposed to be vested in the union.” The Federalist, New York, January 19, 1788. https://guides.loc.gov/federalist-papers/text-41-50 (accessed June 27, 2024).

[iii] Frederick C. Leiner, “Yes, Privateers Mattered.” U.S. Naval Institute, March 2014. https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2014/march/yes-privateers-mattered (Accessed June 27, 2024).

[iv] “Declaration Respecting Maritime Law.” Paris, April 16, 1856. https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/assets/treaties/105-IHL-1-EN.pdf (accessed June 27. 2024).

[v] United Nations, “United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.” November 16, 1994. https://www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/closindx.htm (accessed June 27. 2024).

[vi] Courtney Bonnell and David McHugh, “How are Houthi seizures in the vital Red Sea shipping lane impacting global trade?” The Times of Israel, December 14, 2023. https://www.timesofisrael.com/how-are-houthi-seizures-in-the-vital-red-sea-shipping-lane-impacting-global-trade/ (accessed June 27, 2024).

[vii] Joint Chiefs of Staff, “Joint Publication 1-02: Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms.” Washington D.C., November 8, 2010, as amended through February 15, 2016. https://irp.fas.org/doddir/dod/jp1_02.pdf. (accessed June 27. 2024).

[viii] For example, during the American Civil War, the Union implemented a comprehensive blockade of Confederate ports, known as the “Anaconda Plan.”

[ix] Thomas Dent, “The Strait of Malacca’s Global Supply Chain Implications.” Institute for Supply Management, November 21, 2023. https://www.ismworld.org/supply-management-news-and-reports/news-publications/inside-supply-management-magazine/blog/2023/2023-11/the-strait-of-malaccas-global-supply-chain-implications/#:~:text=The%20volume%20of%20trade%20that,third%20of%20all%20worldwide%20trade. (accessed June 27. 2024).

[x] World Economic Forum, “These are the world’s most vital waterways for global trade.” February 15, 2024. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2024/02/worlds-busiest-ocean-shipping-routes-trade/#:~:text=Around%2094%2C000%20ships%20pass%20through,of%20all%20traded%20goods%20globally. (accessed June 27. 2024).

[xi]U.S. Energy Information Administration, “World Transit Chokepoints.” Updated June 24, 2024. https://www.eia.gov/international/analysis/special-topics/World_Oil_Transit_Chokepoints (accessed June 27, 2024).

[xii] U.S. Energy Information Administration, “China Analysis.” Updated November 14, 2023. https://www.eia.gov/international/analysis/country/CHN (accessed June 27, 2024).

[xiii] Aaron Bazin, “The Dark Fleet: A Glimpse into the Shadowy World of Illicit Shipping.” Strategy Central, July 3, 2024. https://www.strategycentral.io/post/the-dark-fleet-a-brief-glimpse-into-the-shadowy-world-of-illicit-shipping?postId=5c5a4691-fe7a-4380-b396-b511646dc500 (accessed July 5, 2024).

[xiv] Maurice K. DuClos, “Duc’s Notes on U.S. Proxy Warfare over Taiwan,” unpublished manuscript, March 10, 2022.

[xv] U.S. Pacific Fleet, “About Us.” https://www.cpf.navy.mil/About-Us/ (accessed June 29, 2024).

[xvi] Joint Staff, “Joint Concept for Competing.” Washington D.C., February 10, 2023, p.v.; as published by Small Wars Journal on February 26, 2023, p. vi. https://smallwarsjournal.com/blog/joint-concept-competing?utm_source=pocket_saves (accessed June 17, 2024).

[xvii] Sun Tzu, “The Art of War.” Chapter 6: Weak Points and Strong. https://classics.mit.edu/Tzu/artwar.html (accessed June 30, 2024).

[xviii] Craig Singleton, “Mapping the Expansion of China’s Global Military Footprint.” Foundation for Defense of Democracies, 2023. https://www.fdd.org/plaexpansion/

[xix] Pichayada Promchertchoo and Rhea Yasmine Alis Haizan, “Analysis: Thailand’s proposed land bridge project easier than Kra Canal idea, but steep challenges await.” Channel News Asia, October 20, 2023. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/asia/thailand-srettha-thavisin-land-bridge-project-port-malacca-strait-canal-3860941 (accessed July 3, 2024).

[xx] US Code, Title 10 – Armed Forces, section 167 https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2011-title10/pdf/USCODE-2011-title10-subtitleA-partI-chap6-sec167.pdf

[xxi]Brandon J. Weichert, “U.S. Navy’s New Ford-Class Carrier: How to Waste $120 Billion.” The National Interest, May 9, 2024. https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/us-navys-new-ford-class-carrier-how-waste-120-billion-209857 (accessed July 5, 2024).