Semper Fi or Semper Fib? What Bullyville’s McGibney Really Did in the Marine Corps

Bullyville founder’s military claims don’t match reality

NOTE: This piece first appeared on FrankReport.com.

By Frank Parlato

James “Bully Hunter” McGibney likes to say the Marines made him into the “scorched earth” defender he is now, hunting bullies across the world. The Marine Corps taught him how to fight online.

“Sometimes you have to be a bully to stop bullies,” he said.

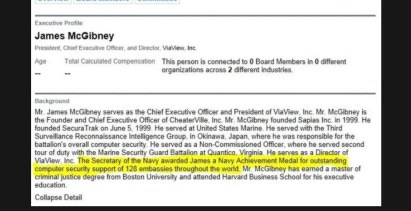

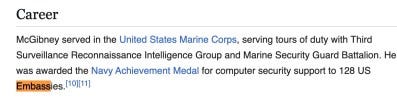

He told Wired and Newsweek that he was nineteen when the Marines assigned him to the Third Surveillance Reconnaissance Intelligence Group in Okinawa. Teenage James was responsible for the entire unit’s computer security. At twenty, he was handling computer security at Quantico. Newsweek even reported that he “was responsible for the cybersecurity of 128 embassies throughout the world.”

Imagine that: embassies scattered across multiple continents, all guarded by one corporal barely old enough to legally rent a car.

His old Wikipedia (2017) page versions show his emabassy protection status, though updated verisions quietly eliminated the claim.

Semper Fi or Semper Fib: What the Records Actually Show

Then the actual Marine records came out.

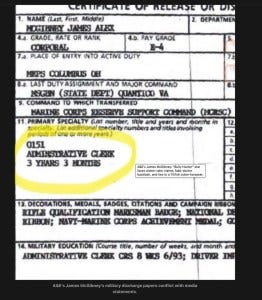

The records put him at Marine Security Guard School in Quantico, scheduling classes, handling attendance, and coordinating with instructors. There was nothing about intelligence work. Nothing about cyber operations. Nothing about overseas duty.

The paperwork listed him as an administrative clerk, MOS 0151. His DD-214 called him a clerk.

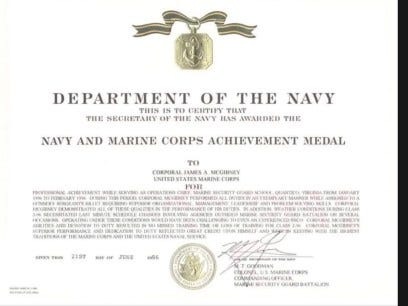

His Navy–Marine Corps Achievement Medal citation said he worked through “last minute schedule changes” in bad weather in Quantico from January to February 1996 and credited him with “scheduling, logistics and classroom coordination.” It said nothing about 128 embassies.

But for babysitting a training schedule through a rough patch of winter weather.

No Okinawa. No embassies. No cybersecurity. He was an administrative clerk.

His service record included four decorations. The Achievement Medal practically thanks him for making sure Class 2-96 got to school on time. In another universe, perhaps, he saved the world. In this one, he saved a calendar.

His military specialty, there is no ignoring it, was 0151 — administrative clerk. In the mid-1990s, the men who handled battalion-level computer security were senior enlisted Marines, warrant officers, or men trained in intelligence or signals. Embassy network security fell to Staff Sergeants, Gunnery Sergeants, or the Colonel in charge of the entire Embassy Security Group.

His DD-214 showed three years and three months of active duty. He left as a corporal.

His awards: Rifle Qualification Marksman Badge- the lowest passing score on the rifle range.

National Defense Service Ribbon, which is automatic.

The Good Conduct Medal is awarded after three years of service without an incident of misconduct.

Marines who served in Okinawa carry ribbons and unit awards from III MEF or SRIG. McGibney had none.

But the cyber war stories helped build the image of a man who said the Marines taught him to fight on the new battlefield. He sports a large tattoo of the flag-raising on Iwo Jima on his back.

Semper Fi or Semper Fib: The Embassy Math Problem

Maybe the records missed something. He said he managed cybersecurity for 128 embassies.

The U.S. has 172 embassies. McGibney says he handled cybersecurity for 128 of them as a teenage corporal. Do the math: that’s three-quarters of American diplomacy. If you count all diplomatic posts — 268 — then he still claims fifty percent. A corporal guarding half the U.S, diplomatic secrets?

Let’s talk about who normally handles cybersecurity for embassies. It’s not the lowest-ranked NCO in the building. You don’t hand the keys to 128 embassies to a corporal.

But the story keeps getting told because it sounds “cyber” and heroic. Meanwhile, the real cyber guys — the 02xx, 26xx, 86xx Marines — were the ones doing the actual intelligence, signals, and computer security.

Semper Fi or Semper Fib: The Anti-Bullying Hero With a Bullying Past

His military mythology didn’t hold up, but his internet persona was just getting started. Then the Internet hands him a gift: Hunter Moore’s revenge-porn website. McGibney buys the domain, shuts it down, and suddenly he’s the Saint of Anti-Bullying.

McGibney would become the hunter of bullies, the vanquisher of online villains, the man who shut down a notorious revenge-porn empire while running a remarkably similar operation of his own.

So what do we have?

A man who hates bullies.

A man who became famous shutting down a bullying site.

A man who ran his own bullying site before that.

A man who invented a military mythology that evaporates under modest sunlight.

His public persona became a sort of comic-book version of morality: the bully who bullies bullies because someone has to do it. So we end up with two James McGibneys: The one in the interviews—the mythic cyber-sentinel forged in Okinawa, standing watch over embassies from a terminal at Quantico. And the one in the records—the clerk who kept the classroom lights on and the rosters straight.

The discrepency between his public persona and the actual DD-214 is striking. Managing cybersecurity for 128 embassies as a corporal would be absurd in any era, but especally in the 90s when those roles requiered senior enlisted or officers. The irony of an anti-bullying advocate building his credibility on exagerated military service is pretty wild.