LUTHMANN NOTE: This is a massive legal development. TikTok has effectively waived Section 230 immunity for any future harms caused by Danesh Noshirvan to TikTok account holders and anyone else. Now, Danesh’s victims can plead that the platform crossed the line from neutral hosting or moderation into helping develop the unlawful content or scheme itself, rendering it an “information content provider” for the harmful material within the meaning of 47 U.S.C. § 230(f)(3).

Under the “material contribution” doctrine, § 230 does not apply where a platform materially contributes to the illegality of the content, such as by structuring its system or conduct so that the unlawful activity is facilitated or built in. Fair Hous. Council of San Fernando Valley v. Roommates.com, LLC, 521 F.3d 1157, 1166–68 (9th Cir. 2008) (en banc). Reinstating a previously deplatformed account in knowing violation of internal enforcement rules is not merely “letting speech exist,” but a commercial relaunch—restoring monetization, increasing distribution, steering traffic through recommendations or featured placement, and offering revenue-share incentives—in a manner that materially contributes to fraud, harassment, extortion, or other coordinated wrongful conduct where amplification and monetization are integral to the harm. Likewise, where a platform does more than host content and instead participates in developing or optimizing deceptive or wrongful content, § 230 immunity is unavailable. FTC v. LeadClick Media, LLC, 838 F.3d 158, 174–76 (2d Cir. 2016). Facts showing that the platform coached creators, structured monetization gates or payout triggers tied to engagement with unlawful content, provided special access or tools, or offered “creator support” that shaped content strategy would further support an inference that the platform affirmatively developed the unlawful scheme.

In short, by reinstating an account in knowing violation of its own rules for the purpose of restoring monetization, and by taking affirmative commercial steps that go beyond publisher discretion, the platform plausibly became a participant in the harmful conduct and thus at least a partial content developer under § 230(f)(3). See 47 U.S.C. § 230(f)(3). Would-be plaintiffs may also invoke recognized limitations on § 230, including liability based on a specific enforceable promise to keep an account deplatformed, sounding in promissory estoppel rather than publication liability, Barnes v. Yahoo!, Inc., 570 F.3d 1096, 1107–09 (9th Cir. 2009); failure-to-warn claims premised on knowledge external to the postings themselves, Doe v. Internet Brands, Inc., 824 F.3d 846, 851–53 (9th Cir. 2016); narrowly framed product or design claims where the defect is separable from publication functions, Herrick v. Grindr, LLC, 765 F. App’x 586, 590–92 (2d Cir. 2019); and, in exceptional cases, aiding-and-abetting theories requiring conscious, culpable participation and substantial assistance tied to the wrongful act, Twitter, Inc. v. Taamneh, 598 U.S. 471, 491–507 (2023).

This piece is “TikTok’s Danesh Noshirvan Liability” and was first available on FrankReport.com.

By Frank Parlato

(FORT MYERS, FLORIDA) – Eight days after TikTok permanently banned Danesh Noshirvan, the mega influencer set for trial in March in a Fort Myers federal court, he’s back on TikTok.

Same account. Same @ThatDaneshGuy. Two million followers. Ninety-one million likes. He is posting new videos as if nothing happened, broadcasting from the TikTok account that told him—and the world —that it no longer exists.

In one of his new videos, Noshirvan holds up TikTok’s ban notice on screen. It reads, “Your account has been permanently banned, and you can no longer access TikTok” — while using TikTok to show it.

He’s complaining that TikTok won’t restore his account, on TikTok, from the account they won’t restore.

TikTok’s Danesh Noshirvan Liability: The Ban Was Real

TikTok’s automated enforcement system, the AI layer that governs account status, still registers Noshirvan as permanently banned. When queried, the system confirms the ban is active.

The ban came after TikTok’s Trust and Safety division — led by Suzy Loftus, the platform’s Head of U.S. Trust and Safety and a former San Francisco interim district attorney — reportedly received a federal judge’s sanctions ruling against Noshirvan. That ruling found that Noshirvan acted in “subjective bad faith” and used his platform to “incite harassment and intimidation.”

The federal sanctions order stands. The $62,320 penalty remains unpaid.

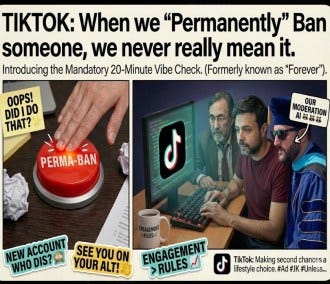

TikTok’s Danesh Noshirvan Liability: Five Bans, Five Resurrections

According to Rebecca Martin, who has monitored Noshirvan’s TikTok activity for five years, TikTok has banned Danesh at least five times.

Most TikTok users who get permanently banned have to start over. Millions of creators with followings have had to accept that reality.

Noshirvan gets banned, then unbanned, which eliminates any theory that this is a fluke.

TikTok’s Danesh Noshirvan Liability: How Does a Permanently Banned User Post From a Permanently Banned Account?

There are a few possible explanations. None reflects well on TikTok, which claims it has spent $2 billion on trust and safety.

Explanation 1: Someone Inside TikTok Let Him Back In (True)

TikTok’s ban enforcement is handled by an automated system. The system still shows Noshirvan as banned.

Someone with backend access — an engineer, a trust and safety employee, or someone with administrative privileges — could have reactivated the account without updating the enforcement record. This could mean a rogue employee acted independently, a policy reversal was made without documentation, or someone inside the company did Noshirvan a favor.

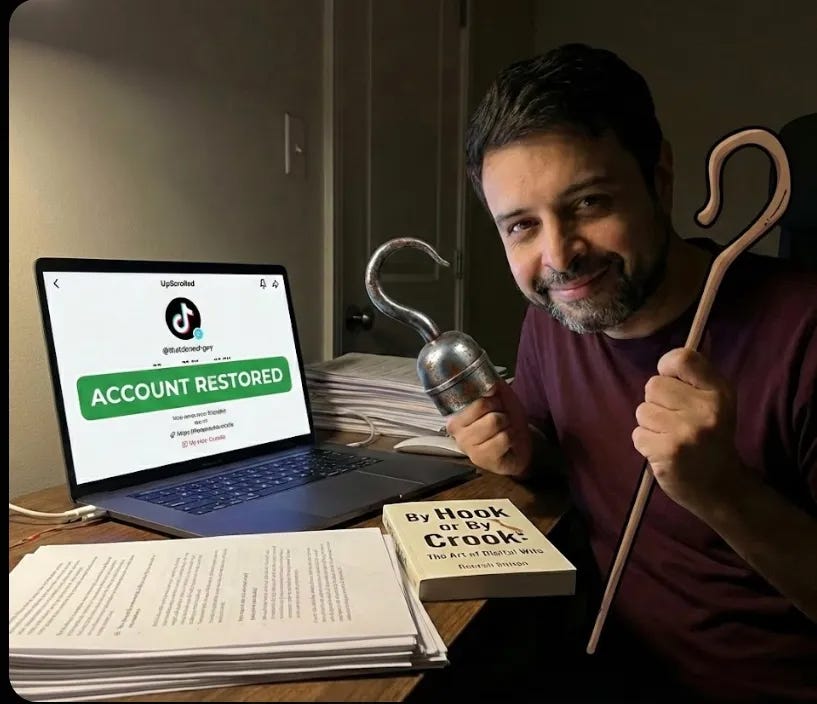

LUTHMANN NOTE: If Danesh is to be believed, a TOP EXECUTIVE at TikTok (or Byte Dance, its parent company) reinstated his account.

Explanation 2: He Tricked His Way Back In (True)

The ban worked for eight days. Noshirvan was locked out. Someone or something unlocked the account. His restoration might have involved deception.

TikTok employs thousands of customer service agents worldwide. Most of them handle routine complaints: a hacked account, a lost password, a video wrongly removed. They can restore accounts. What they may not have is the context to know why a particular account was banned in the first place.

Noshirvan could have contacted TikTok support through a back channel, posing as someone else, submitting a fabricated claim of wrongful termination, or simply working the system until he reached a low-level agent who saw a locked account and a convincing request. The enforcement system never gets updated because the restoration didn’t go through the team that imposed the ban.

TikTok also has automated account recovery systems — email verification, phone verification, and identity confirmation. If Noshirvan found a way to trigger one of those processes that overrode the ban without routing through the appeals team, he could have reactivated the account without any human at TikTok approving it.

LUTHMANN NOTE: If Danesh is to be believed, he advanced material misrepresentations and targeted harassment at TikTok/Byte Dance executives, maybe the AI-driven bot network he’s used in countless cases to harasshis victims.

Explanation 3: Through Illegal Hacking (Not Yet Ruled Out)

There is another possibility. He may have phished an actual TikTok employee, obtaining login credentials through a fake email or a spoofed internal request, and used that access to unlock himself. This would constitute a federal crime under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act.

All three scenarios point to the same problem. A man who was sanctioned by a federal judge for inciting harassment used some combination of deception and persistence to undo a permanent ban.

LUTHMANN NOTE: If Danesh is to be believed, the targeted harassment is illegal. He may also have engaged in hacker activities (along with known associates like Mr. James McGibney), as was detailed in the Rebecca Martin case.

TikTok’s Danesh Noshirvan Liability: The Defanged Danesh

The Frank Report’s Danesh Chronicles, along with the investigative work of Rich Luthmann and Joey Camp, have exposed that Noshirvan’s 2 million followers are mainly bot networks. The purchased followers are the subject of jokes. When Danesh targets someone now, the targets know the mob isn’t real. The angry comments are bots. The phone calls are auto-dialers. The one-star reviews are software.

What He Did With His Resurrection

Noshirvan didn’t use his return to show restraint or demonstrate that TikTok’s second chance, however he obtained it, would be used responsibly.

In the video posted from his supposedly banned account, he launched a “Special Report” attacking Jeremy Wilson, one of the victims currently suing him.

The behavior that got him sanctioned by a federal judge resumed the moment he reappeared.

TikTok’s Danesh Noshirvan Liability: TikTok’s Choice

Meantime, a ban notice said, “You can no longer access TikTok.”

He’s accessing TikTok.

So what does that notice really mean? Evidently, nothing at all.